Supplement to the Manual of Orthic Shorthand [Orthographic Cursive]: The Cambridge System

by Hugh L. Callendar, M.A., Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. 1892.

Hugh L. Callendar’s Supplement to the Manual of Orthic Shorthand by Jeremy W. Sherman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at https://jeremywsherman.com/. Original PDF scan

Preface

It is now nearly a year since the publication of Orthographic Cursive. The approval with which it has been greeted on all sides has more than fulfilled the author’s expectations, and repaid him for the years which he has spent in the endeavour to devise a system of shorthand sufficiently simple for general use.

The want of a brief and convenient title for the system has been very generally felt. It has been decided to adopt the title of ‘Orthic’ in place of the somewhat cumbrous ‘Orthographic Cursive.’

A society called the ‘Cambridge Shorthand Society’ has recently been started for the study and propagation of Orthic. It has been placed under the management of Mr W. Stevens, of the Commercial and Technical Institute, Ranelagh Road, Ealing, W. Manuscript magazines are, at present, circulated among the members, and serve to provide practice in reading and writing the system. It is hoped shortly to publish a magazine printed in Orthic, and to establish a central school in London for the benefit of clerks and others who wish to perfect themselves in the reporting style, and to utilise the system for business purposes. In the meantime teaching for various centres can be arranged with Mr Stevens, the Principle of the Ealing Institute.

—H. L. CALLENDAR

June, 1892.

Supplement to the Manual of Orthic

Introduction

The object of the following pages is to supply fuller explanation and illustration of the methods of abbreviation given in the Manual as ‘Hints for the Reporting Style’ and to provide advanced writers of the system with additional matter for exercise and reading practice.

Some students appear to think that a phonetic system must necessarily be briefer and simpler than an orthographic. Others appreciating the superior simplicity of the orthographic method are apt to wonder why shorthand was ever made phonetic. It has therefore been thought necessary to explain these points more fully for the benefit of those who may not have read the author’s previous publications on the subject.

Advantages of the Orthographic Basis

An Orthography, that is to say a definite standard of spelling, is the necessary groundwork of any practical system of writing. It is essential, both for the sake of rapid automatic writing and to secure ease and certainty in reading, that each word should always be spelt in the same way. In this way alone can it be written without conscious thought, and read without hesitation.

The author has insisted on this point, and illustrated it at some length in previous publications, particularly in the introduction to the Manual of Cursive Shorthand1 (Phonetic). Every word of that introduction will apply equally to the present system, except that it is orthographic and not phonetic. The student who wishes thoroughly to master the principles of Orthic, and to learn how and why it differs from other systems of shorthand, will find in the introduction to the Phonetic Manual much that is interesting and instructive, and that will be of material assistance to him. The proof and explanation of the above statement, having been already given therein, need not be repeated here. It is only necessary to point out its bearing on the question of an orthographic as opposed to a phonetic basis for shorthand.

Simple, definite, and familiar

Every system of shorthand must in one sense be orthographic. There must be a correct outline for each word. Every departure from this rule entails a certain loss of efficiency, and a systematic violation of it results in hopeless confusion.

It is evidently much simpler, if possible, to adopt the commonly received orthography as the basis of spelling for a shorthand system, than to elaborate a new phonetic standard. The common spelling is already familiar to everyone, and is a practically perfect standard in point of strictness and uniformity. Phonetic spelling, on the other hand, is to many people extremely distasteful and difficult to learn. It is, moreover, even when learnt, an uncertain and unsatisfactory standard2 owing to varieties and changes of pronunciation.

That is the main and decisive point. The simplicity and definiteness obtained by adopting the orthographic basis make it far preferable for general use to the phonetic. There are several minor advantages, however, which should not be overlooked.

Easily represents names and foreign languages

A phonetic system is quite unable to cope with any peculiarities of spelling, or to give any adequate representation of proper names. It is also very difficult to adapt to the pronunciation of a foreign language. Orthic, as shown in the Manual, can be used, almost without change, for writing any foreign language that is spelt with the common alphabet.

Longhand abbreviations directly usable

Another very practical advantage of Orthic is that all the familiar longhand abbreviations can be at once utilised. The majority of the examples given in the list of ‘Examples of Abbreviations’ are simply transliterations of those in common use, and being already familiar require no learning.

Equal to any phonetic system

It is commonly urged in favour of phonetic spelling that so much is gained in point of shortness by the omission of mute and silent letters, and by using simple signs for diphthongs and other compound sounds. This argument as applied to shorthand is somewhat misleading. All phonetic methods of abbreviation, such as tho for though, brot for brought etc., in so far as they are convenient and clear, are naturally utilised in any orthographic system. Common diphthongs and combinations are also naturally represented by simple curves. The characters of the orthographic alphabet can also be grouped on the principle of representing similar sounds by similar signs, thus securing whatever advantages a phonetic system may claim in this respect.

Solves the harder problems

From the inventor’s point of view, the real advantage of a phonetic system lies in the fact that it is much easier to construct. The early inventors could not find sufficient material for their alphabets in the way of characters that would join easily and clearly. They got out of the difficulty by rejecting what they called duplicate or superfluous letters, such as c, j, q, x, and by omitting all the vowels, or expressing them by detached marks. This was really only a method of cutting the Gordian knot, and could not result in the production of a system adequate and suitable for general use. The comparative case of constructing a system on this basis is, however, undoubtedly the true explanation of the extraordinary prevalence of systems of this type.

It is much more difficult to find sufficient stenographic material for a complete phonetic system, providing joined characters for both vowels and consonants. The difficulty of constructing a complete orthographic system is of the same kind, but greater, owing to the great number and variety of different combinations to be provided for.

As early as 1887 the author fully recognised the advantages of an orthographic basis in point of simplicity, and had made many unsuccessful attempts to construct such a system; but at the time of writing the introduction of the Manual he did not fully realise the difficulties that phonetic spelling presents to the majority of students. He was therefore content to abandon his orthographic labours, and to acquiesce in the generally prevailing opinion (as expressed in the Manual, p. 19) that a system of shorthand to be simple, consistent and complete must be phonetic, since it is almost impossible to make a system represent consistently and simply the endless variety of combinations in the common spelling. A correction in the above passage suggested by two or three eminent shorthand authorities, conducted in striking out the word ‘almost’ before impossible. The author however, having at length succeeded in solving the problem to his own satisfaction, is now of the opinion that he had somewhat over-rated the impossibility.

No need to learn phonetic spelling

Very shortly after the publication of Cursive, it became evident that the difficulties of the majority of learners were almost entirely phonetic, that the system was otherwise extremely simple and very easily acquired. The author therefore set to work again in a more systematic way. A most elaborate analysis was made of the common spelling of English and several foreign languages. The relative frequencies and modes of occurrence of all the possible combinations of letters were tabulated. By means of this table a great variety of different methods and arrangements of characters were tested and rejected, or emended and improved. After about a year of trial and failure an alphabet was at length evolved, capable of satisfying all the conditions previously laid down.

Subsequent experience of Orthic has served only to confirm the author’s expectations. The testimony of learners is unanimous as to its great simplicity in comparison with any phonetic system. Teachers and school-masters in particular declare most strongly in its favour. They find, as might naturally be expected, that besides bring more easily learnt, it has not, like phonetic systems, any tendency to spoil the learner’s spelling.

Phonetic spelling in itself is undoubtedly a useful educational subject and a valuable aid in teaching correct pronunciation. This argument is often advanced in favour of phonetic shorthand. But it has been shown that there is no necessary connection between the two; and it is manifestly unreasonable to saddle shorthand with unnecessary difficulties in order to teach at the same time a subject which many people have no need or desire to learn. In any case the work of both teacher and learner would be much simplified by keeping the two subjects separate.

Ordinary Style

The Ordinary Style of Orthic is intended for general use and for purposes of correspondence and communication between different writers of the system. The rules have been made as simple and definite as possible, so that any word can be correctly written in one way only. It is particularly desirable that writers should keep as far as possible to the ordinary style in correspondence, and that they should not introduce reporting abbreviations of their own devising.

Since the publication of the Manual the methods of abbreviation given under ‘Hints for Reporting’ have been very thoroughly tested by experienced writers of the system. Many of these methods have been found to be so convenient and safe for purposes of correspondence that it has been decided to admit them into the ordinary style. The following list contains a fuller explanation and illustration of the abbreviations which have been thus admitted.

It should be observed that the use of these additional abbreviations is optional. Those who prefer it may continue to write the full ordinary style as developed in the Manual, which is quite brief enough for general purposes. But if they correspond with advanced writers of the system, they must be prepared to meet with any of the following methods of abbreviation.

Teachers are recommended to instruct their pupils thoroughly in the full ordinary style, before introducing them to the advanced style developed in this Supplement. They should also make beginners write between double-ruled lines at first, as explained in the Manual, ‘The Two Sizes of Character.’ This is of great assistance in forming the characters neatly, and in distinguishing correctly between the two sizes.

General Method of Abbreviation

The general method of abbreviating Orthic as given in the Manual is the same as that ordinarily employed in longhand, namely, to write the first syllable of a word and, if necessary, to indicate the termination by writing the last letter or two separated by a small interval from the rest of the word. Experience has shown that abbreviations made in this way are at once the most suggestive and the most readily extemporised. The free use of this method of abbreviation is rendered possible in Orthic by the full expression of vowels in the outlines. In systems of shorthand which have no adequate means of expressing the vowels, it would obviously be quite inadmissible.

In correspondence, this method must of course be used with reason and moderation and with due regard to the context. It should be restricted to very common words or to words frequently repeated and specially related to the subject of the letter. In taking notes intended only for private use, it may much more freely employed.

Examples of abbreviations for common words such as may safely be used in correspondence are given in the list of ‘Examples of Abbreviations.’ The method of curtailment may be applied to short words as well as to long ones. In the case of short words containing a characteristic long vowel of diphthong it is usually best to keep the vowel (e.g. rea for read, rou for round, cou for count), but in the case of very common words for which abbreviations are already current in longhand, it is often better to follow the longhand usage (e.g. rt for right, mst for most, pt for part, pnt for point, cd for could). It may be remarked that, as in longhand, the same abbreviation may in some cases be used for two or even three different words provided they are different parts of speech such as would necessarily be distinguished by the context. Thus hd is used for had and head and also for the termination -hood, wd for would and world, mst for most and must, mt for might and for the termination -ment. In most systems of shorthand this principle is applied, by the wholesale omission of vowels, to an altogether unwarrantable extent. In Taylor’s or Pitman’s a single combination of consonants such as ls may stand for any one of twenty or thirty different words. The principle in itself is good and reasonable, but we would caution writers of Orthic against the abuse of it.

Phraseography

Time is frequently saved and legibility increased by joining words together in phrases without lifting the pen. This is a powerful method of abbreviation in the hands of experienced writers, and is specially applicable in the case of Orthic owing to its lineality and facility of joining. Experience has shown, however, that beginners are apt to run riot with all sorts of impossible and useless phrases to the great detriment of the speed and legibility of their writing. The number of possible and useful phrases is so great that it is impracticable to publish and exhaustive list showing what phrases may be used in the ordinary style. The simplest and best general rule for a beginner to follow is not to use phraseography at all in correspondence until he has made himself perfectly familiar with the system.

Supra-Linear Writing

This signifies writing a word above the line, out of its natural position, to indicate the omission of a prefix. It is a method of great simplicity and power if properly applied.

Initial th as explained in the Manual is already expressed in this way, supplying clear and systematic abbreviations for a very special class of common words peculiar to English. It is found, however, that the use of this method may be very largely extended without any risk of clashing. It will be observed that all the following applications of the method are merely special cases of the general method of abbreviation ‘by mode’ as explained in the Manual.

Eve

The words:

-

every

-

evening

-

event

-

evident

-

evil

and their derivatives are abbreviated by the V-Mode, in the same way as ever, by omitting the eve and writing the rest of the word above the line.

Exception: Even is written e’en  , to distinguish it from than or then.

, to distinguish it from than or then.

Be

This prefix is peculiar to a special class of English words, and may also be expressed by writing above the line.

The word be is expressed by a dot above the line  ; been and being by n

; been and being by n  and straight ‑ing

and straight ‑ing  ; the former will not be found to clash with than.

; the former will not be found to clash with than.

Per-, pro-, pre-

These prefixes, being Latin, will not clash with any of the above English prefixes, and may be expressed in the same way with great saving of time and space. [E.g.  person,

person,  present,

present,  promise.]

promise.]

Pre- and pro- are distinguished from per, if necessary, by retaining the vowels e and o. The cases, however, in which it is necessary to make the distinction are very rare.

When any of these prefixes occur in the middle of a word after another prefix, as in the words unbelief, compromise, etc., they are expressed by Mode (1), that is to say by writing the terminal portion of the word close above and to the right of the initial prefix. [E.g.  comprehend.]

In the prefixes super, supra, hyper, the per is similarly expressed.

comprehend.]

In the prefixes super, supra, hyper, the per is similarly expressed.

The allied prefix pri may be expressed in the same way as pre in some common words. [E.g.,  private.]

private.]

Para, peri

These Greek prefixes may also be expressed by supra-linear writing for the same reason. Peri is distinguished by retaining the i; it may be regarded as a special case of per.

Examples of these prefixes will be found in the list of ‘Examples of Abbreviations.’

Other Prefixes and Slurs

Acqu

Written aqu  .

.

Adj

Written aj  .

.

Adv

Slurred into one large character compounded of d and v as explained in the Manual, ‘Hints for Reporting,’ ‘Slurring.’ [E.g.,  advantage.]

advantage.]

Com, con

Expressed by a dot on the line written close in front of the word, as explained in the Manual, ‘Hints for Reporting.’

[Jeremy: As far as I can tell, this is not actually explained there. You could infer it, but it’s not explained.] [E.g.  common,

common,  conc(ern)ing.]

In taking notes, the dot may generally be omitted or expressed by Mode (2).

In correspondence it should be retained.

conc(ern)ing.]

In taking notes, the dot may generally be omitted or expressed by Mode (2).

In correspondence it should be retained.

In compound prefixes, such as incom-, discom-, etc., the com- or con- is expressed by Mode (2).

Circum

Written cir  followed by a short break to represent cum. Circe

followed by a short break to represent cum. Circe  is the the regular longhand abbreviation for the word circumstance.

is the the regular longhand abbreviation for the word circumstance.

Magna, magni

Written m, the rest of the word being placed below to indicate the g. (Mode (3), Manual, ‘Hints.’) [E.g.  magnify.]

magnify.]

Mb

May be written with a single character somewhat like mp  , but beginning and ending on the line

, but beginning and ending on the line  . (See the list.)

. (See the list.)

Mis-

Written ms, omitting the i.

Nch, sch

These combinations may be written without an angle or break. (See inch  , such

, such  , school

, school  , in the list.)

, in the list.)

Tch

The t may always be omitted in this combination. [Jeremy: As far as I can tell, not a single example of this rule appears in this book!]

Trans

Written trs, as in longhand. [E.g.  transact.]

transact.]

Terminations

In accordance with the general method terminations are indicated by writing the last letter or two detached from the rest of the word. Thus the common terminations ‑ent, ‑ence, ‑ency, ‑graph, ‑ism, ‑ship, ‑wise, are written ‑t, ‑ce, ‑cy, ‑ph, ‑m, ‑p, ‑se, respectively. (See the list.)

Ness

This termination should be written ‑ess detached, by the general rule, and not ns as given in the Manual. [E.g.  goodness.]

Detached n and ns can then be used, as in longhand, for the expression of the common terminations ‑ation and ‑ations.

goodness.]

Detached n and ns can then be used, as in longhand, for the expression of the common terminations ‑ation and ‑ations.

Ve, ‑ive

This common termination is expressed by a dot above and to the right of the word to indicate the v.

(Mode (1), Manual, ‘Hints.’) [E.g.  arrive.]

When the word is inflected the last letter of the inflection is substituted for the dot.

(See gives

arrive.]

When the word is inflected the last letter of the inflection is substituted for the dot.

(See gives  , given

, given  , selves

, selves  , etc. in the list.)

, etc. in the list.)

Ge, ‑dge, ‑age

These and derived terminations are similarly expressed by a dot below and to the right to indicate the g.

(Mode (3), Manual, ‘Hints.’

See also knowledge  , agent

, agent  , etc. in the list.)

, etc. in the list.)

Gn, gram

Indicated by n  and m

and m  respectively written below (Mode (3)) to indicate the g, as in the termination ‑ight.

(See foreign

respectively written below (Mode (3)) to indicate the g, as in the termination ‑ight.

(See foreign  , sign

, sign  , in the list.)

, in the list.)

Examples of Abbreviations

[J: Note that each brief is a link to itself, to aid in teaching fellow writers.]

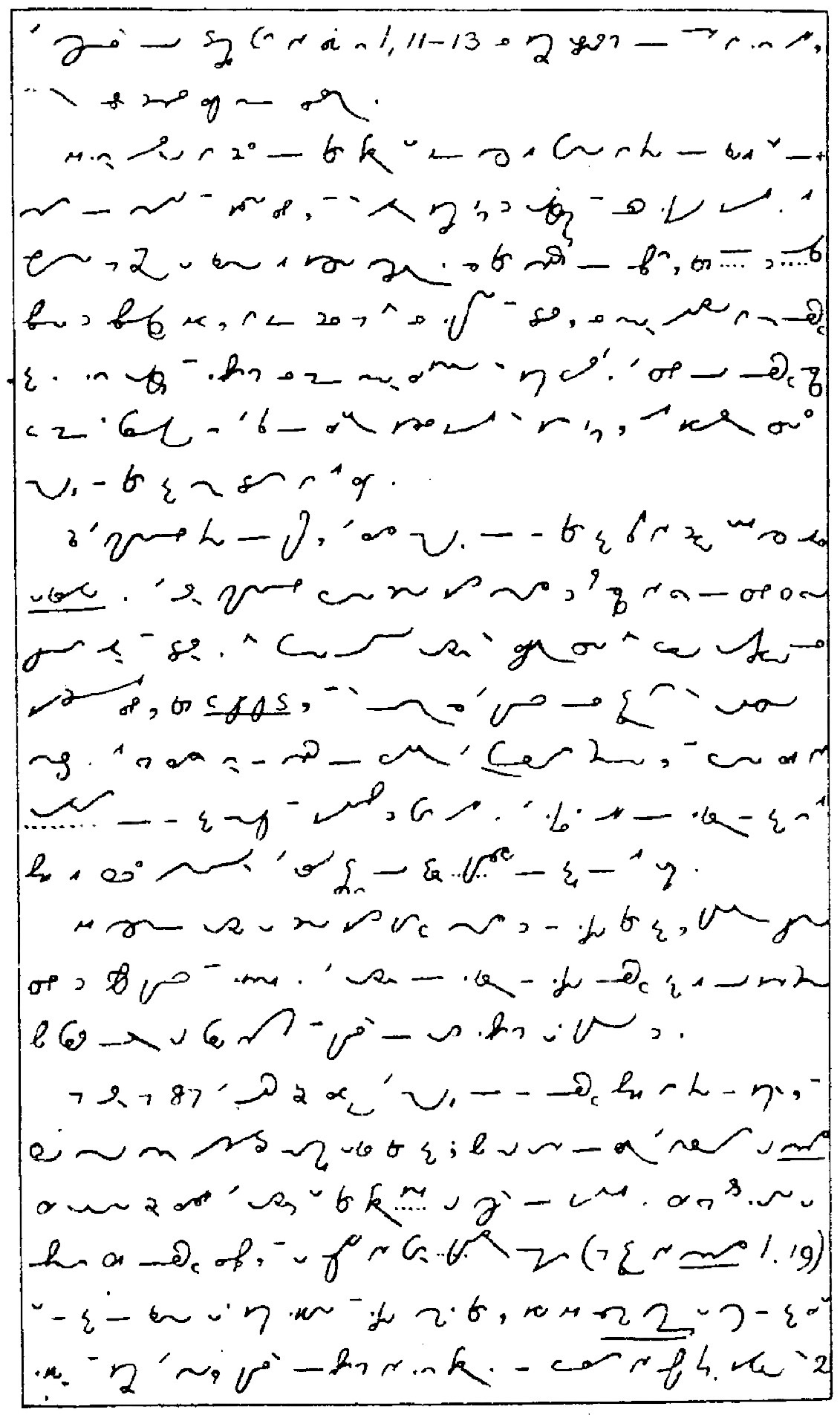

Specimen: Ordinary Style, Abbreviated

This specimen is the introduction to this book rendered in the abbreviated ordinary style that is its subject. It comprises the entire chapter ‘Advantages of the Orthographic Basis’ and the start of ‘The Ordinary Style.’ The earlier text itself serves as the key.

The new sentence is a variation on one occurring later in the ‘General Method’ chapter: ‘In reporting or taking notes for private use much greater latitude may be naturally allowed.’

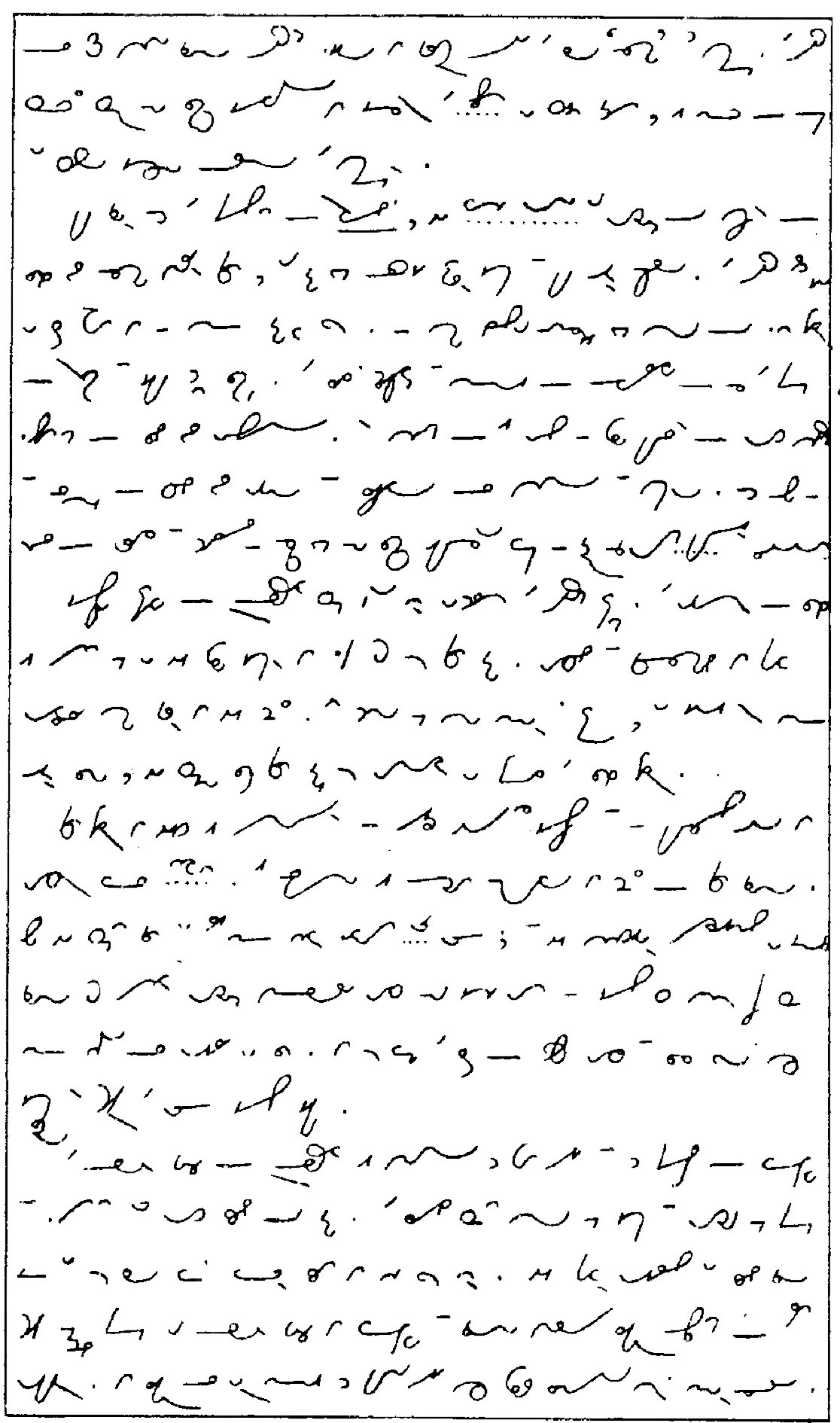

Specimen: Notes on Reporting

Key

[Jeremy: As in the Manual, the Reporting Specimen did not have a key. This section is my own contribution.]

Notes on Reporting

(page 1, line 1) The reporting style of Orthic is in no way essent(ial)ly dif(ferent) fr(om) the ord(inar)y (line 2) style. There-is li(tt)le n(e)w t(o) learn and n(oth)ing to unlearn. It’s simply an extension of-the same (l. 3) pr(inciple)s and methods of abbreviation, and-the acquirement of speed and facility is merely a (4) qu(estion) of prac(tice).

[Freely yet judiciously abbreviate]

(5) The most important and generally useful method of abbreviation is the general method already (6) explained. It may be very freely used in reporting with due regard to the context. (7) Half the art of reporting depends on the judicious use of the context. (8) The good reporter acquires an instinct which tells him how he may scribble and abbreviate (9) recklessly without fear of subsequent misreading. Common or repeated words (10) may be very generally abbreviated but uncommon or rare words should be carefully written. (11) It’s of no use to burden the memory with special abbreviations for rare words (12) however long and awkward they may be. Beginners often waste a great deal of time (13) and ingenuity in devising special contractions for such words as bijection, trinitarianism, (14) sesquipedalian, and-the like. The absurdity of such-a proceeding is too obvious (15) to need comment.

Modes

(16) The use of modes (1) and (3) (except in the special cases (17) already given) should be almost entirely restricted to the expression of V and G respectively. (18) Many students appear to have misunderstood the principles of their application and some have even (19) gone so far as to write all words beginning with p, b or v above the line omitting (page 2, line 1) the initial letter. This is manifestly absurd. The initial letter of a word is (2) usually the most important for its identification and should therefore be retained — except in (3) one special case namely that of a com(mo)n prefix. Such-a prefix being common to a large class (4) of words is a less use for purpose of identification and may therefore be (5) suitably expressed by the method of supra-linear writing.

(6) In-the middle of a short word G or V may be conveniently expressed by the (7) mode as in sre = severe, ren = regain, st = sight, (8) but in-the case of longer words it’s generally better to keep the G or V if it forms (9) part of-the first syllable or root of-the word, and only to express it by mode (10) if it occurs in a subsequent syllable. For instance it’s better to write several = (11) sev than sral, similarly regn = regulation, nev = benevolent not nlent (12) but in abbrte = abbreviate, elte = elevate, intelce = intelligence, reln = religion (13) the V or G would be aptly expressed by mode.

Slurring

(14) In addition to the common slurs given in the Manual the fo(llo)wing (15) will be fou(nd) useful:

- double-wide M = man (compare double-wide D = td)

- double-wide M and y = many

- (16) w and double-wide M = woman

- u and double-wide M = human

- double-wide M and uf = manuf(acture)

- double-wide M and ey = money

- (17) ct-blend = ct

- f hooked up at end = fs

- k hooked up at end like initial w = ks

- cl = chl

- clofm = chloroform [J: I originally thought this was “chroroform”, and expected the L to be inside the CH to stay below the line of exit. In fact, this “chl” together with “fr(anything)” underscores that Callendar considered the direction the circle is traced rather than whether the circle is above or below the exiting line that distinguishes R from L.]

Short Vowels

(18) Short vowels may often be slurred especially in terminations,

- double-wide M and r = manner

- (19) upr = upper

- n-nl = national.

T may generally be slurred in-the terminations ty (20) and th, thus duy = duty, wih = with, ohr = other.

(page 3, line 1) Examples of other slurs are;

- long O and gy = ology

- tmow = tomorrow

- (2) c long-ou r = counter

- ul = until

- i n s long-d = instead

- nst = next.

Repeated Letters

(3) Repeated letters may often be omitted when abbreviating especially if the termination contains (4) the last letter of-the root and can be joined. This principle has always been freely used in long (ha)nd abbreviations. (5) Thus

- este = estate

- ulte = ultimate

- circe = circumstance

- instute = institute.

Other Suggestions

(6) It has been proposed to use the mode of writing below the line (7) for the expression of-the common prefixes de and di, the latter being distinguished by retaining the i. (8) Thus

- ifer = differ

- fer = defer

- isfun = dissatisfaction

- ft = defendant [J: I totally expected “defeat”, which amply demonstrates the next point.]

(9) This method however should not be used in correspondence but restricted to private notes.

E and i

(10) E and i may often be distinguished without dotting the i by writing the letter more (11) steeply than e. Compare

- illegib(le) with eligible

- inter with enter

- ill with ell.

Shading

(12) There can be no doubt that the device of shading or thickening a character (13) is not sound for general use. Some writers however are of opinion that it may occasionally be (14) used with advantage in reporting. If used it’s most appropriately applied to express a combined R or L (15) thus [using capitals to represent shaded characters]

- Fme = fr(a)me,

- Coss = cross,

- pP = ppl,

- Pac = prac(tice),

- oD = old;

- (16) aTghr = altghr,

- Am = arm.

The method however is not to be generally recommended.

Lastly

(17) The most important rule of all in reporting practice is never to use a mode or an (18) abbreviation that causes hesitation or waste of time, not to worry about trifles; and to practise (19) writing from dictation and transcribing till your notes become perfectly fluent and cursive and legible. (20) A study of-the examples which follow will probably be more useful than many pages of hints.

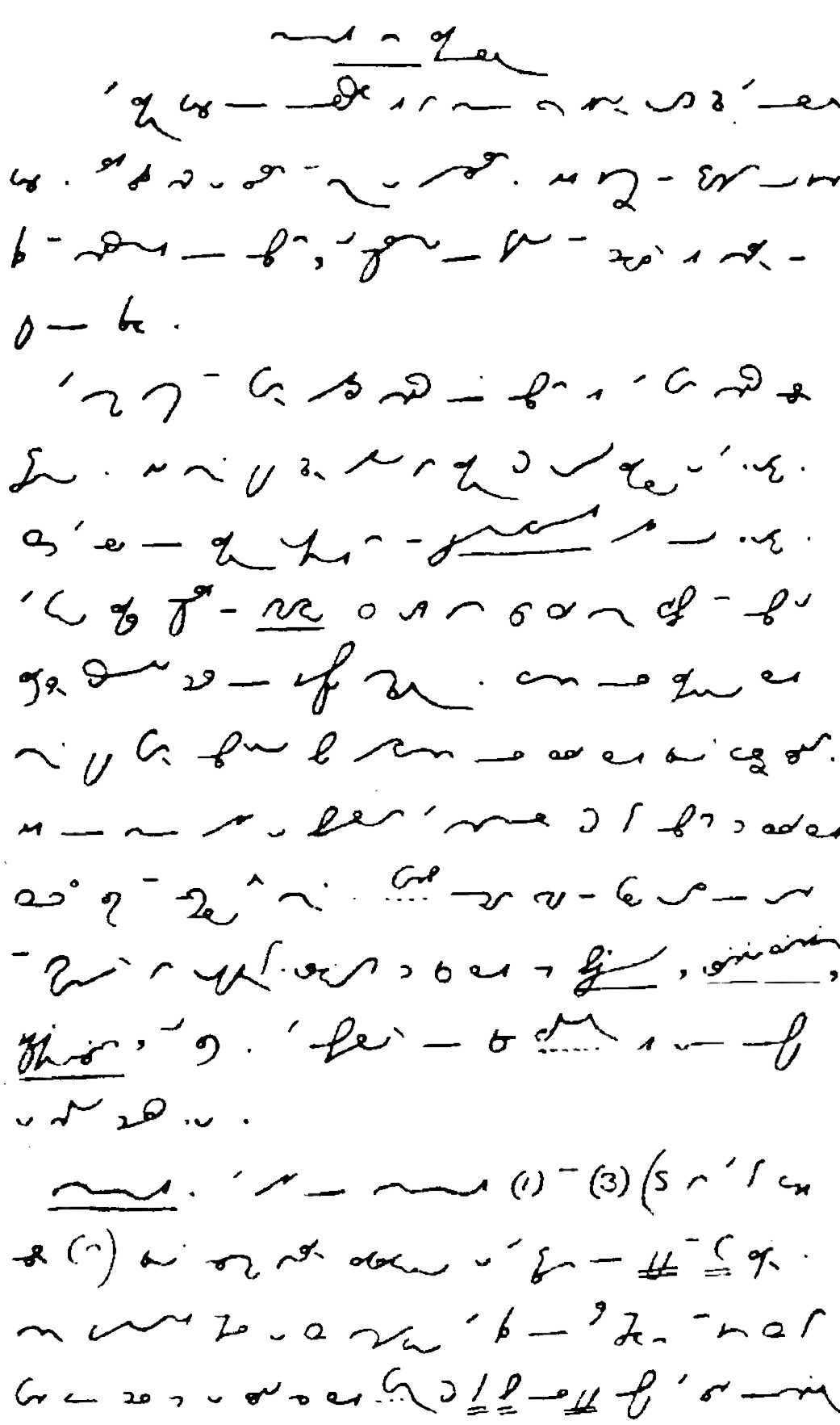

Specimen: Notes of a Speech by Lord Dufferin at St Andrews

Page 1

Key to Page 1

The Rector, who was received with cheers, said that he had determined that the best return he could make to those who had shown him so much kindness, but to whom he knew he was incompetent to communicate anything worth their attention, in regard either to science or letters, would be to give them, in as simple and unpretending a manner as he could, such practical hints in regard to some few of the matters which would affect their start in life as his own personal experience might furnish.

The first piece of advice, then, that he would give was to endeavour to reach a practical conception both of the length and of the shortness of life; he urged upon them to get clearly into their heads the fact that life is a definite circumscribed period of time, sufficiently long to get a great deal done in it, and yet not long enough to oppress them with the idea of exhausting and unending effort. He asked them, in the next place, to try and frame for themselves beforehand as clear and correct a conception as circumstances might permit of the natural incidence, and ultimate conditions of whatever careers they were determined to follow, being careful at the same time, before they chose their profession, to get a right knowledge of their individual aptitudes, and of the extent of their powers, for he was convinced that their usefulness, as well as their happiness, depended upon their work being done in a congenial atmosphere; and that it was much better to choose a humbler, less promising, or less remunerative walk in life, in which they were certain of personal satisfaction, than to commit themselves to a more ambitious employment which might, perhaps, prove distressing to their tastes and unsuited to their faculties.

He impressed upon them strongly the necessity of attending to their health, maintaining that the healthiness and robustness of their nerves and mental fibre were as worthy of cultivation as those of their corporeal faculties. In that way they would keep themselves free from those morbid, sentimental, and vicious growths which left a human being neither man nor woman.

Regarding the acquisition of languages, he was inclined to range himself on the side of those who would retain not only Latin but also Greek as an essential part of the education of every gentleman. Nay, if one were to be compulsorily admitted, he would prefer dropping Latin rather than Greek, for the literature of Greece had been the quarry out of which the brightest gems in the writings of their modern authors had been extracted. He adverted to the necessity of their acquiring a knowledge of, at all events, one modern European language, and there could not be any doubt that that language should be French, for not only was its literature the

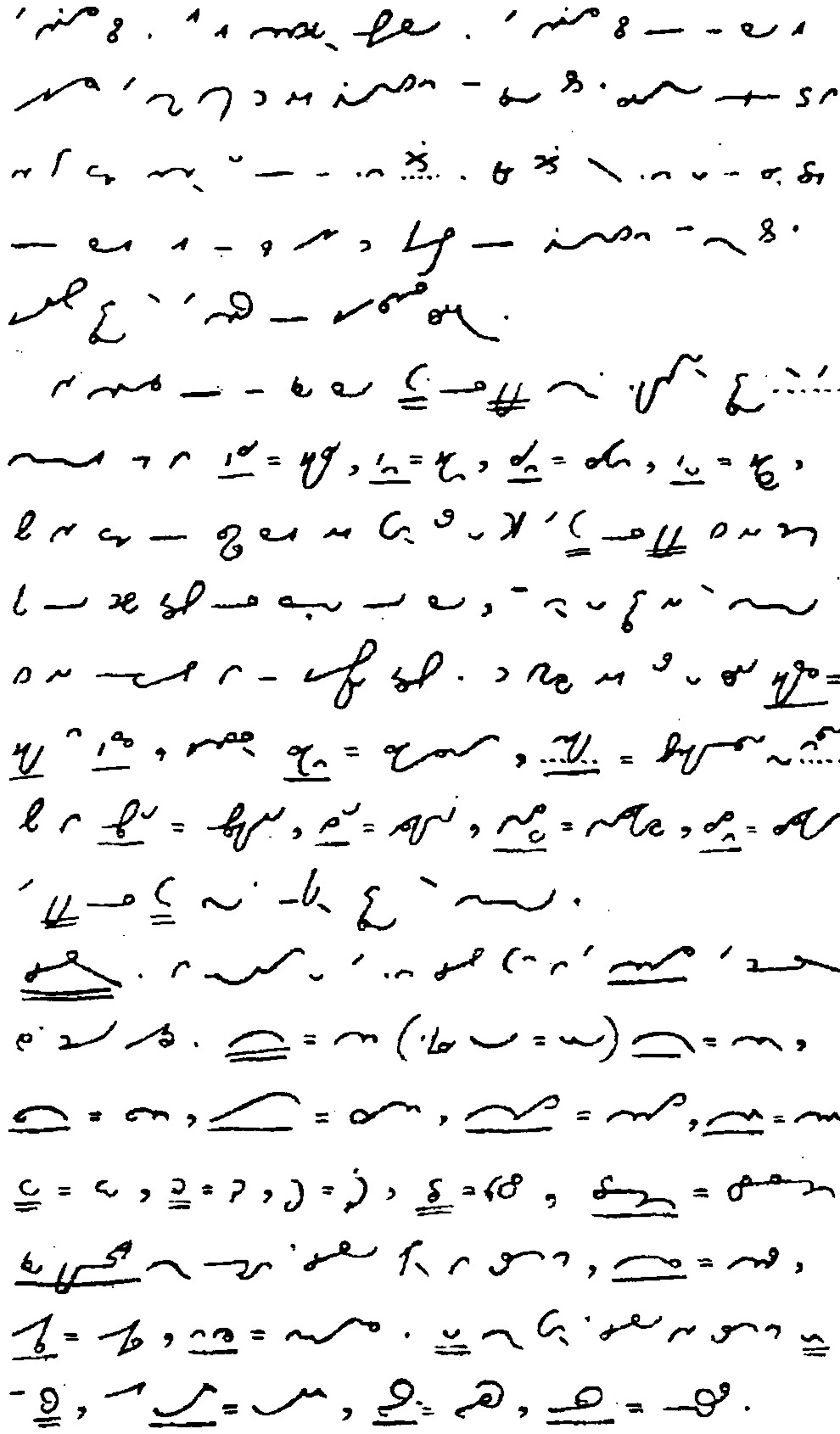

Page 2

Key to Page 2

most diverse and admirable possessed by any European community except their own, but it had long been accepted as the common channel of communication between European nations.

But far more important than the acquisition of any foreign tongue was the art of skilfully handling their own. Already Providence had issued its decree that English should be the predominant language of the globe — in other words, the man who wrote a good book, or made a good speech in English, would command for all time what was already the greatest audience known to history, and which eventually would cover the better part of three of the five continents of the world. There was one golden rule which he would venture to insist upon — namely, that in the first place, before putting pen to paper, they should compel their own mind to hammer out an absolutely clear and distinct conception of the thought they wished to express, and that then they should put it into the simplest and least Latinised words that came to hand, without giving a thought to what was called style, and confining their attention to the attainment of only two objects — conciseness and lucidity. There was one other useful rule which he would also recommend to all young writers, no matter what might be the nature of their composition, whether books, speeches, sermons, lectures, or addresses — namely, that after they had written them they should cut them down by about one-third. Probably there were few books, fewer still sermons, and certainly no speeches, that had ever been produced or delivered which would not have been much improved by being considerably curtailed.

With regard to public speaking, the first essential principle was undoubtedly practice. He had often heard experienced members of the House of Commons remark on the extraordinary improvement which practice had produced amongst those whom necessary circumstances or their own courage and ambition had induced to persevere in imposing themselves upon a long-suffering audience. He adverted to their writing an extempore speech beforehand, and said they should not send it to the reporters, before it had been delivered, as once was done by an acquaintance of his, who, after all, never got an opportunity of speaking.

His Lordship concluded by mentioning two further rules of conduct — namely, the cultivation of the spirit of justice, and, of the sentiment of chivalry. The secret of lifelong happiness was not, as was generally said, to keep one’s illusions as long as possible, but to preserve the conviction that one’s “illusions” were the only realities, and that their destruction was tantamount to their becoming the victims of a vain and empty dream. But with knightly purity and white-robed justice for their companions, the magic light would neither waver nor fade from their path.

Specimen: Verbatim Report of a Speech

Key: Lord Salisbury at the Mansion House

My Lord Mayor, my noble colleague challenged me to tell you what were the changes of policy of her Majesty’s Government. Well, we are to meet in Cabinet to-morrow, and of course I shall have the opportunity of explaining them to him more distinctly when we meet. But I may tell you that my task will be an easy one, because they are represented by zero. There are no changes in the policy of her Majesty’s Government.

We are quite satisfied with the result of our policy in Ireland. And we think that the statesman who has been principally associated with that policy, Mr Arthur Balfour, may retire from the immediate supervision of it with a consciousness of the best bit of four years’ work that has ever been done by a statesman. And I am bound to say that what we have recently seen in Ireland has not altered our opinion. What we have seen has not made us think that a domestic legislature in Ireland will be distinguished by peace or order, or an abstinence from blackthorn, or a freedom from the curse of ecclesiastical domination. Therefore I have to reply to my noble friend that I see no reason to change our policy with respect to Ireland.

With respect to our foreign affairs, there is always a certain difficulty and responsibility, because the speaker is apt to be suspected of intending to assume the mantle of a prophet. I desire entirely to disclaim that intention. We have had a good deal of prophecy of late — they call it meteorology. We are told of things that are certainly to happen in a year’s time. Well, I am not here to discuss those prophecies, but I think confident predictions when they are to the advantage of the predictor are sometimes a mistake, for fortune is fond of flouting such confidence.

But, at all events, whatever we may think of domestic affairs, with respect to Foreign affairs I will speak only of the present what I know; and with respect to the present I will say that there is not on the horizon a single speck of a cloud which contains within it anything injurious to the prospects of peace. In fact, it seems to me that the warfare of nations, if you are to judge by the interest they take in the subject, is slowly changing its object and its field, and that it is the industrial competition which chiefly occupies in these days the chancellaries and diplomacies. The great subjects of consideration are those Treaties of Commerce which are to expire next year; the great question is what tariffs will the various nations adopt with regard to each other. And though, with respect to material warfare, I think we can hold out to you the most promising anticipations, as far as our present prospects go, with respect to this industrial warfare, which has for its weapons protective legislation, and has for its prize the markets of various countries, I am afraid we must be content to occupy for a time a peculiar and isolated position.